When Ido Simyoni was 15, doctors diagnosed him with fibrous dysplasia, a condition where scar-like tissue forms instead of bone and causes benign tumors. Simyoni’s condition affected his skull, and over the years, several tumors invaded his forehead, eye socket and the bone below his brain.

Doctors removed the tumors and replaced the bone as needed. But as time passed, the replaced bone would shrink, causing dents in his forehead. It also made him susceptible to infections that could easily reach his brain.

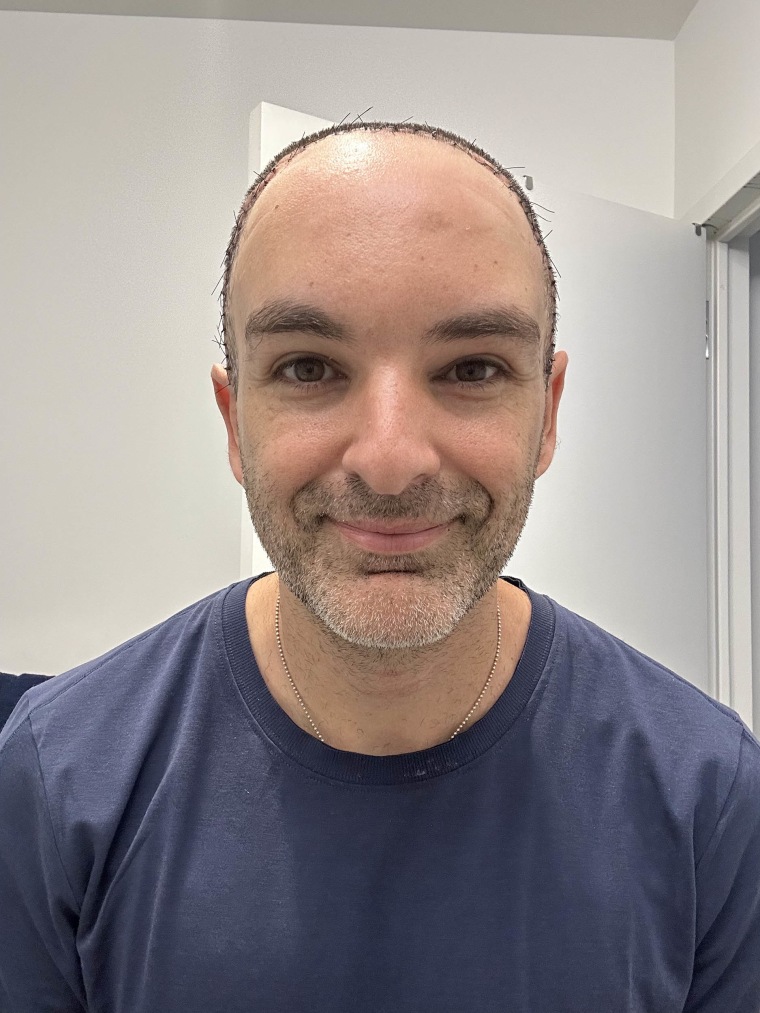

Still, Simyoni learned to live with the condition’s effect on his appearance and health — until one morning in mid-2022 when he “woke up very, very swollen,” Simyoni, 41, of Queens, New York, tells TODAY.com. “That indicated to me that something is wrong.”

So he decided to find a new neurologist — someone well-versed in fibrous dysplasia because his case is extra complicated, given its proximity to his skull and brain.

Two head surgeries later, Simonyoni is living life to the fullest and really to take on his next goal: running all six World Major Marathons in 2024.

“It was a very, very tough year to go through, and now I’m getting to the other side of it,” he says. “I set myself this very ambitious goal. … I believe in myself. I hope that my body (will) not betray me.”

Rare condition causes a lifetime of problems

When Simyoni was 15, acquaintances noted that his left eye looked smaller. Close friends and family didn’t notice it, but after a while, the comments began bothering him.

“I’m telling my mom, ‘Everyone is saying that my left eye is becoming smaller, and I don’t know what they’re saying.’ And literally as I’m saying it, I’m touching above my left eye and below it and I feel a bump,” he says. “I touched this on the other eye. … I don’t feel that bump.”

Simyoni visited his doctor, who sent him for an X-ray, and he was eventually diagnosed with fibrous dysplasia.

This condition starts when some babies develop in the womb and a gene mutates, which stops the maturation of bone-forming cells, according to the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. As these children grow, they develop abnormal fibrous tissue in their bones. It can happen in multiple places in the body or just one. Simyoni had it only in his skull, which is more dangerous than other locations.

At 15, he had his first surgery to remove a tumor.

“They actually (did surgery) through the eye,” he says. There was only one doctor where he lived in Israel familiar with his condition.

Simyoni hoped that after this surgery, he would be OK, but when he was 17, doctors found another tumor that was growing into the dura mater, the protective covering of his brain.

“It didn’t enter the brain, but it was outside,” he says. “They removed that tumor then, and then they told me, ‘You’re done. That’s it.’”

For almost a decade, he lived without needing any more surgery. Then when he was 26, he developed another tumor. At first, doctors didn’t believe him, but Simyoni could sense the changes.

“I had to tell them, ‘I feel something inside. I know it’s back,’” he recalls. “When they opened me, they saw the tumor.”

That tumor grew into the dura mater and tore it, so doctors stitched it shut before replacing his forehead with bone they had taken from the top of his skull. While recovering in the neurological intensive care unit, he leaked too much cerebrospinal fluid, a liquid that protects the brain from infection, and came close to dying.

“I remember saying goodbye to my mom and my sister,” Simyoni says. “Thankfully, the doctors brought me back.”

Since that surgery almost 15 years ago, the bone replacing his forehead started to shrink, causing his head to have visible indentations and eventually leading to frequent infections in his nasal cavity and headaches. Still, he didn’t let that stop him from enjoying life and he became a marathon runner.

Then last year, he noticed he needed more medication to quash his daily headaches. At first, he hesitated to visit a doctor.

“I spent so many years of my life in hospitals, so I really didn’t want to do any more checkups. I didn’t want to go to a neurosurgeon,” he says. “I didn’t want to be that guy with a tumor.”

When he woke with a swollen face, Simyoni knew he couldn’t ignore his health any longer. He visited several doctors to see how they could help him. Many recommended procedures that would improve the appearance of his forehead, but one doctor, who is both a neurosurgeon and plastic surgeon, suggested two surgeries.

He told Simyoni that the first procedure would completely resolve any lingering infections that could reach his brain and the second that would fix his skull.

“I’ve never heard of any (neurosurgeon) that is also a plastic surgeon,” he explains. “I discovered that it’s actually very rare.”

Fibrous dysplasia and its treatment

Fibrous dysplasia is a rare congenital disease of the bone that often affects the cranial facial structures, Dr. Netanel Ben-Shalom, a nuerosurgeon, at Northwell Lenox Hill Hospital, tells TODAY.com.

“Some would call fibrous dysplasia a tumor that can change the structure of the facial skeleton,” he says. “It can grow into sizes that are very big. And if it grows, it’s compressing on critical structures, like the brain or the eyes, and needs surgical intervention.”

Fibrous dysplasia impacted Simyoni’s frontal sinus, his eye socket and the bone that sits under our frontal lobe.

Simyoni required complex procedures. The skull base had deteriorated, meaning the barrier between the interior of the nose and the brain was permeable. When Simyoni woke up swollen, it was because the bacteria in the nose had traveled into the skull, causing a persistent infection. Without intervention, the infection could turn deadly.

“It could have (been) a life-threatening situation if that infection would have … affected his brain,” Ben-Shalom says. “He would have severe meningitis, encephalitis and bad consequences.”

That’s why Ben-Shalom knew a two-surgery solution would work best. In the first procedure, the surgeon removed the bone used to reconstruct his forehead, cleaned out all the infection and repaired the barrier between the nose and the brain. That meant that Simyoni looked a little different for a few weeks.

“He had no forehead — no bony structure, no skull in the forehead,” Ben-Shalom says.

After six weeks of antibiotics and recovery, Ben-Shalom performed the second surgery where he used a customized, 3D-printed piece to reconstruct Simyoni’s skull.

“We had to use hardware to pretty much build his forehead,” Ben-Shalom explains. “That’s safer and that’s why we’re using alloplastic (implants) these days compared to the patient’s own bone.”

Recovery

Simyoni’s first surgery was in May and the second in August. Having a hole in his forehead between surgeries affected his confidence.

“It’s almost feeling like you’re naked. … I’m going outside and putting myself out there and something is missing,” he says. “Now, I can smile about it. But back then, it was very scary.”

Simyoni says he’s “slowly getting back to himself,” and began running again. In 2024, he plans to run the six world major marathons — New York City, Chicago, Boston, Berlin, Tokyo and London. He has earned a spot in all of them except for London and New York City. He ran the six marathons last year before his surgery and finished several under three hours.

“I’m a very positive person, but I also really like to prepare myself for the worst,” he says. “I have to prepare myself that I won’t be able to run anymore, so that’s why I wanted to finish the six marathon majors.”

Simyoni wants to inspire others and hopes his story encourages others grappling with health conditions or other difficulties.

“It’s your decision how you want to live. It’s your decision of how you want to fight,” he says. “I want for people to hear about me and see me and see that despite going through all this craziness … I am going to come out stronger.”